"The word citizen has to do with city, and the ideal city is organised around citizenship - around participation in public life."

Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking

As another cable-car swung above his head, Daniel, a skinny teenager with black curls tumbling out under his baseball cap, was telling us about the streets in which he grew up: "you couldn't go out after dark, the gangs controlled the area and we were at war with the neighbourhood just down the hill.”

The image he creates is at odds with what we can see on this sunny day in the community of Santo Domingo Savio, high up in the hills of Medellin: schoolchildren doubling up on the swing-set, a few tourists milling around with cameras, mango stalls running a brisk afternoon trade and walls alive with colourful murals. It seemed, well, so normal.

However, such normality was a distant thing in Santo Domingo and other barrios in Medellin as little as a decade ago, and Daniel's story was the reality for many in a city divided by violence.

And yet in 2015, Colombia's second-city – once the murder capital of the world - is today polishing off several international accolades for inclusion, innovation and urban planning. It is the cause celebré of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Harvard Foundation and troubled cities throughout Latin America are looking towards the mountains of Medellin for inspiration on how to improve themselves.

We joined Martin from Palenque Tours to discover more about Medellin's metamorphosis.

a city at rock bottom

As with so many stories of Medellin's turbulent past, ours begins with Pablo Escobar, whose name is synonymous with a drugs trade that crippled the country.

In the late 70s and early 80s, against the back-drop of a civil-war, weak, corruptible state institutions and an irrepressible Western appetite for recreational drugs, Medellin became the epicentre of the global cocaine trade. And Escobar was the undoubted king-pin.

So here, on a quiet residential street, in front of a derelict white tower-block, we start our tour. Gutted by scavengers searching for hidden millions, it is difficult to imagine that the custom built Edificio Monaco (penthouse on the top, jail cells on the bottom) was once the cartel's nerve centre, and Escobar's home.

It was from here that all manner of atrocities were ordered - the deaths of countless of civilians, police, judges and several presidential candidates. It was from here that Escobar orchestrated his personal war.

At the height of his power in 1991, Medellin bore witness to more than 6,000 homicides - a rate of 380 per 100,00 people. To put this in context, such a rate in London would equate to 38,000 murders annually (in 2014, London actually had under 100).

Martin tells us that the conflict between drug gangs, the state and other armed forces became so bad, that airports were duty bound to advise you not to visit Medellin before you boarded a plane to Colombia; this was a city on its knees and with a gun pointed at it.

Today, the building – armed 24-7 by the police – is only an empty relic of the city's bloody past and a popular stop on Escobar tours. The fact that the government has no idea what to do with it now – develop, demolish or let it remain as some sort of 'museum' – is perhaps influenced by the tourist pesos Escobar's name and notoriety bring in, but maybe having it remain is not such a bad or distasteful thing.

In fact, in a city which is trying so hard to transform its architecture and infrastructure, they need this as a monument to how far it fell.

comuna 13

In this environment of crime and illegality, large swathes of the city were controlled for decades by drug lords or armed militias, and often a working collaboration between the two. The prime example of such a neighbourhood was San Javier - better known as Comuna 13 - the next stop on our tour.

We had first read about Comuna 13 the previous day the at the Casa de la Memoria museum (our number one activity in the city by the way), where a number of the photography exhibits showed it as as a war-zone in 2002. Helicopters firing, soldiers in full combat gear, snipers on the roofs and bloody bodies on the streets.

Historically, this area of Medellin was a complete no-go. The most violent neighbourhood in the most violent of cities, Martin tell us. Control of its clustered steeply sloping streets was held at various junctures by the non-state actors which have plagued Colombia – guerillas, street gangs and narcos - and the government simply wasn't present. 13's location was a key driver of this pitch-battle, with its strategic proximity next to the highway which brings you to the Uraba coast (a key drug-trafickking route) meaning that “those who control the highway decide what enters and leaves the city: drugs, guns, money." And so, those who controlled 13 would control the route.

And this is a place only ten minutes from the Palaces of Justice.

The 2002 Operation Orion saw the government (acting with paramilitaries) lay siege to Comuna 13 to take back power. There is still debate and controversy over how the shock-and-awe operation was undertaken, and over its short and long-term goals, but one thing is clear; it provided a blood-soaked platform for the roots of Medellin's transformation.

Today, the community is accessed via a short bus ride then several outdoor escalators - the type you find in shopping centres. Previously, residents would have had to climb 350+ stairs, but now it's only a three-minute ascent. They act not only act as a symbol of the state's presence in the area – physically they dominate – but as a bridge of sorts to a community once separated from the city.

Although improved accessibility and security were the main factors behind the stairs, tourism has been an unexpected upside. In fact, Martin tells us, more tourists probably visit 13 than Colombians – history, fear and reputation still weighs heavily on locals, whereas tourists don't perhaps realise what the area once was.

We wander around the streets, where the escalators are not the only physical manifestation of the changes of the last few years. The roofs of the houses have been brightly painted after a donation towards the materials, and the old cans now act as flower pots. The street-art covering every inch of wall space is the product of one of a number of arts-based social youth projects aimed at offering 13's kids with an alternative future and place in a society, where previously gangs and violence were the main recruiter. Hip-hop projects also play a big role here.

From grass-roots arts projects such as these, the area now stands out for something different to the violence of previous decades; it is a patch of colour on Medellin's otherwise brown brick city skyline (check out some more of our photography from Comuna 13 here).

innovative infrastructure

We descend the escalators from Comuna 13 contemplating how much we would have avoided this area had we visited five or ten years ago. We catch a bus to the first piece of the puzzle behind Medellin's vision of social change through infrastructure, the metro.

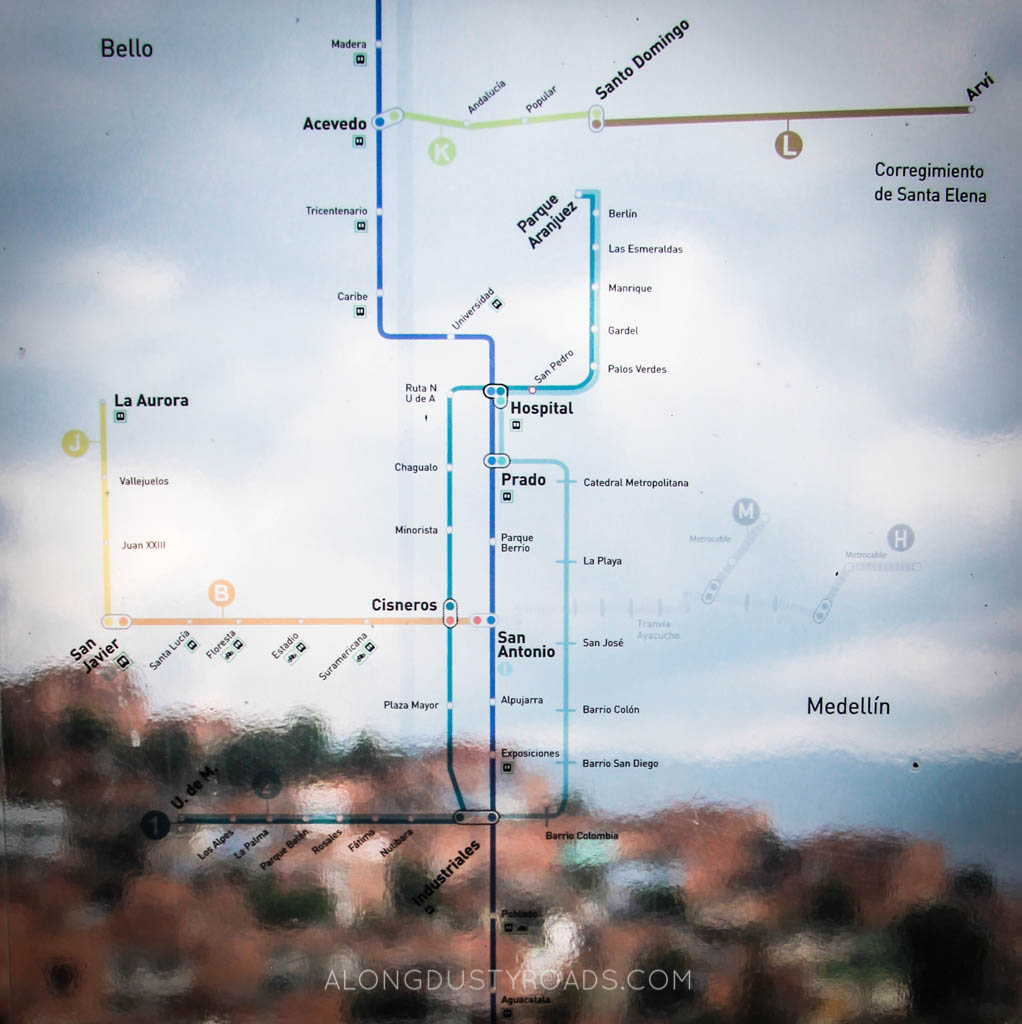

Completed in 1995, it is still the only metro system in Colombia (capital Bogota has plans for one but it will be at least a decade until its up and running), with its two lines travelling overground from north to south and from the city centre to the west. Aside from the obvious economic benefits, the metro began to symbolically dissolve the invisible borders between barrios like 13 and more secure, affluent parts of the city.

During our time in Medellin, we've noticed the immense pride paisas have towards the metro. Andrew's hairdresser positively raved about it and on all our travels, we've never been on such a spotless piece of public transport - you can drop litter in many places in Colombia, but don't you dare on Medellin's metro.

People here clearly respect what it has delivered to the city and what it represents.

As we leave San Javier metro station, we are lifted above the city by Medellin's greatest and most visible accomplishment - the cable car. The first urban transport system of its kind in the world, it is fully linked to the metro system and the price of one journey, anywhere in the city, is cheap at $2,000 (£0.5) or $2,100 if purchased with a bus ticket.

The technology itself is relatively common, with the same type of cable-car system used in Europe and the US primarily to transport the well-off from ski-resort to slope. In Medellin however, this mode of transport had social justice at its core; its purpose was to close the physical gap between the city's poorest and their fellow citizens.

For it wasn't just the drugs, the cartels and chaos caused by Colombia's long-running war, though these are of crucial factors, which led to Medellin having a catalogue of endemic socio-economic issues. The city's geography also played a major role.

Medellin is set in the Aburra valley with steep green Andean hills on every side. Its brick brown buildings are tightly packed and space is at a finite premium. When the population grew at a phenomenal rate during the 20th century, the only way to go for the impoverished or displaced arriving in Medellin was up the mountain. Indeed, there is a saying here; the poorer you are, the higher up the mountain you'll be.

And these hillside neighbourhoods – already physically separated from the rest of the city – became further cut-off when the cartels stepped in and took control. Growing up in these barrios put you in to the most marginalised, most violent, poorest, least educated and most without hope bracket of society, and this negative cycle would reinforce itself again and again over the years.

Rising higher in our six-person cab, we look through the windows and down to the changing urban landscape below. Tightly compressed clusters of buildings snake their way up the hills. Rusting tin-shack roofs, brick buildings, old cement bags acting as insulation, little space and little order. Proper poverty.

The difference from the residential area where we stay in our hostel is marked.

We ask Martin, what difference does this cable car system make to the man in house down below us? He's still poor, he's still relatively uneducated and, for all wants and purposes, his daily life is not going to change that much. Is it?

"Accessibility and inclusion. Before, if he wanted to access the city – his city, let's not forget – then it would take him at least two hours. He was cut off and not part of civic society. Now, he can access the job market, the hospital, the new libraries, the parks for only 2,000 pesos and in 30 minutes.”

We dwell on this whilst we look over the entire city. We still think that for that man in that shack, his opportunities are very limited – improved, yes – but still limited. It's probably too late for him.

But it's the three young boys embarking at the very top – all dressed in the ubiquitous green and white colours of local team Nacional – that make us appreciate what the social transformation through transport is really about here in Medellin. It's for those kids to access the city and to feel part of something – rather than belonging to a pariah neighbourhood – that will see the real difference. Education and opportunity.

Before, they would have been “aliens" in their own city – physically and psychologically separated from the people down in the valley - with little option but to become just another victim to the cycle of Medellin's special brew of crime, poverty and drugs; but now they have some hope. And some is better than none.

Our final stop of the day is on the other side of town, in the optimistically renamed Santo Domingo. Once one of the most dangerous neighbourhoods in Medellin, this is a now a community rebranded with the name of the patron saint of hopeful mothers - a place where mothers have hope for their children, rather than fear.

And it appears hope, and and a lot of hard work, are paying off. At least on the outside, this neighbourhood has been transformed.

Set alongside the smiling families and curious tourists, the Biblioteca Espana dominates Santo Domingo's skyline. A literal beacon of change. And whilst some may argue that this community may have best suited a hospital or school, there is no denying the symbolism.

Daniel's story is not unique. If it were not for the social initiatives, transport developments and gang truces he would at best be part of the violence or, at worse, dead like so many that went before him. Now he is able to meet people from all over the world (as far as India he tells us) and give them a potted history of his home for a few thousand pesos.

Aside from the metro and the cable cars, local government also focused on several other improvements to poor neighbourhoods. Huge public libraries have been built whilst there are free gyms peppered throughout, wi-fi in the parks, free bicycle rental and swimming pools. In Comuna 4, community gardens have been built on top of a rubbish dump.

The long-term aim was not just to change the space above these barrios, but also the space and institutions within them. To turn negative space into positive architecture.

At night, what was once one of the most dangerous areas of downtown, the square is now lit up by a forest of lights, visible to all from above.

The spirit and symbols of transformation around town are tangible and shining.

But what about the substance? One cannot deliver a hagiography about Medellin's transformation; a city once home to so many devils will not now be populated solely by angels.

It still ranks just inside the 50 most violent cities in the world (at number 49 with 26.91 homicides per 100,000 residents). Comuna 13, despite strides of improvement, still witnesses remarkable levels of violence, crime and gang-activity. Several pioneers of the progressive and anti-violence hip-hop initiatives were gunned down, a perceived threat to the gangs which still operate from within its now painted walls.

After the death of one of the rappers - El Duke in 2012 - the residents wrote a public letter saying "Comuna 13 still has not been able to live one day in peace."

You walk through a lot of downtown and it's clear there are still deep-rooted issues of poverty in the city.

Take an afternoon stroll to Plaza Botero - home to a popular art museum - and you'll still see groups of prostitutes and addicts outside the white church, some disconcertingly young.

Scores of homeless young men live underneath the metro lines, whilst one street to the left is a bustling financial district.

Organised crime - centred around cocaine and money laundering - still has a vast operation in the city despite operating less visibly and ostentatiously than in prior decades.

Gangs still stalk and control certain areas and take lives at will.

However, this shouldn't come as a surprise. In a city where systematic violence and illegal activity have formed the backbone of its way of being and reputation for so long, a few cable cars and libraries are not going to be a panacea. Indeed, there are a myriad of reasons and conspiracies which point to gang truces and changes in their methods as far more influential than some innovative mayoral strategies for the reduced crime stats and increased security apparatus.

So let's also be honest about Medellin; this is still a place with problems.

However, name us one major Latin American city which doesn't have its problems. After spending the day wandering around the city with Palenque Tours it is clear that Medellin definitely has something different about it - a positivity, a dynamism and a vision that things can be improved, better, transformed.

Different ways of designing an urban environment, giving modes of transport a social purpose and recognising that fostering better inclusion in a divided society are fundamental tenets to any city's prosperity, and Medellin's achievement is that it is thinking about how to solve all these problems.

Here, they are actively creating solutions on their own and from within. It is the city in Colombia which we, as travellers, would have gone out of our way to avoid only twenty years ago, but in 2015 have we decided to spend one month here.

The identity of of a place, once so ruined, can be transformed and that has, without a doubt, happened here.

Alejandro Echeverri (one of the key men who orchestrated Medellin's transformation) says of his city: "One thing about Medellin is that things happen - for good and bad, but they happen. We replace our own cell structure. Things move. We provide presidents, academics, writers - and drug lords. Pablo Escobar could only have come from here; on the other hand, what we have tried could also have only have started here."

And although it still has some distance to travel, this is a place definitely going up in the world. All we can hope is that tourists now visit to see what it is becoming, rather than dwelling upon what it once was.

palenque tours information

This article was made possible through the insight and knowledge provided by Palenque Tours on their 'Transformation Tour'.

Their tour was complimentary for Along Dusty Roads, however we can only highly recommend them after our own excellent experience. Martin, our guide, was knowledgable, professional and spoke excellent English.

A Colombian-German company focusing on socially and ecologically responsible tourism, they offer a number of tours in Medellin, Antioquia and throughout Colombia. For more information, please visit their website orcontacto@palenquetourscolombia.com

All photos are the property of Along Dusty Roads and cannot be used or reproduced without our permission