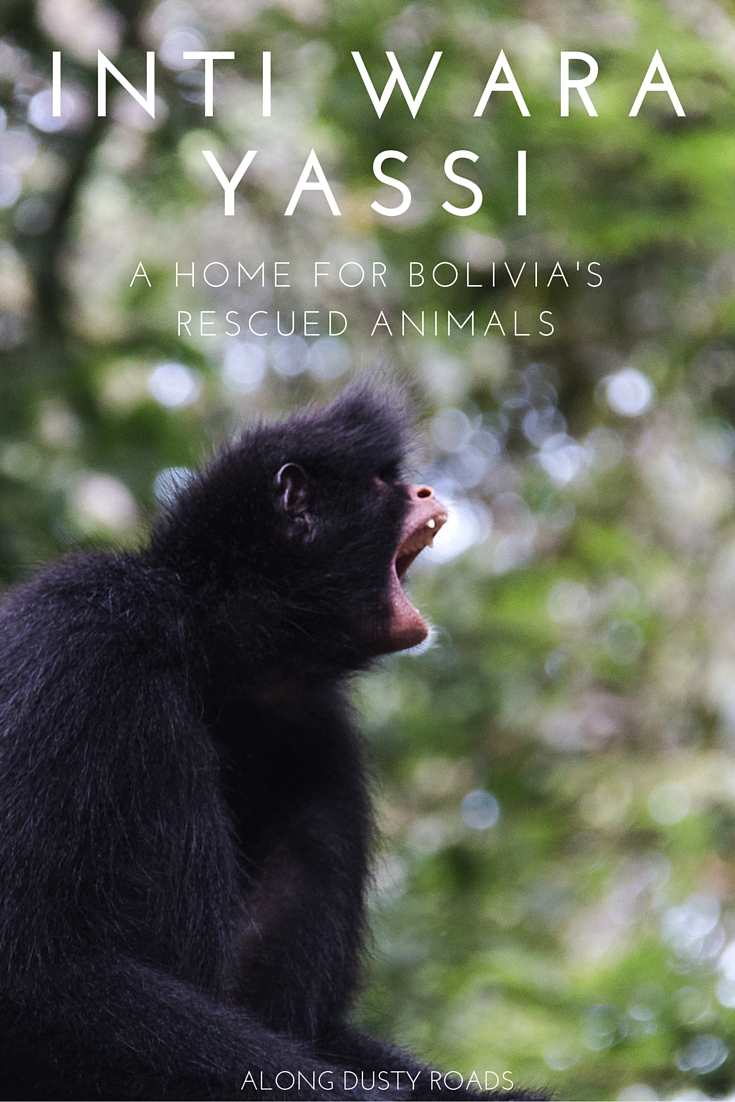

We spent an incredible few days with Inta Wara Yassi, an animal refuge in the heart of the Bolivian jungle.

These are the stories of the animals and the people whose lives have changed forever because of it.

Her name was Bebe.

From her horizontal position on the old wooden bench, she saw us approaching. Leathery black hands folded under her chin, legs dangling off either side, she looked a mixture of bored and laconic. Our chaperone - a smiling Australian volunteer - instructed us to quietly crouch down in the grass and observe.

Bebe rolled off the bench and ambled over to us on all fours. Laying down by Emily's side, she observed us with as much curiosity as we observed her. And, together, in silence, that's how we sat for a few blissful and peaceful moments before Bebe wandered off to explore another part of the jungle she now calls home.

When she first arrived at Parque Machía, few could have foreseen that such an interaction would have ever been possible. Bebe had been found in the streets of La Paz, Bolivia's administrative capital at 4,000m altitude. Shivering and terrified, with her fur matted and clearly malnourished, her presence in the city formed only one part of the rescue team's concerns; the severe bloating around her stomach was a matter of more urgent importance for her well-being.

Investigation by veterinarians established that this beautiful, defenceless female spider monkey had been subjected to repeated sexual abuse by her 'owner'.

Once rescued and relocated, her journey towards rehabilitation was slow and difficult. She was, understandably wary of humans and, in particular, every male. They couldn't come close. Only one person was able to break through to slowly lead and nurture Bebe towards a second chance at an existence where she didn't have to live in constant fear.

As harrowing as it is, her story is not unique; every single one of the animals at Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi (CIWY) - a non-profit Bolivian animal refuge - has such a story to tell. Not all are as shocking as Bebe's, but each lays bare humanity's disrespect towards animals: their greed, their selfishness, their malevolence, their cruelty and their total disregard for their importance in our global ecosystem. And these fortunate unfortunate few are the ones still alive to tell theirs; only three out of every ten animals stolen from the wild survive the ensuing mistreatment they are subjected to in the animal trafficking trade. And of those three, only one will live to make it to their ultimate 'owner'.

Thankfully, there are people, like those at CIWY, trying to make a difference. To rescue, to protect and to educate. We joined their small core of Bolivians staff and rag-tag squad of international volunteers in the rain-forest of Bolivia to understand their work, their struggles and the importance of their message.

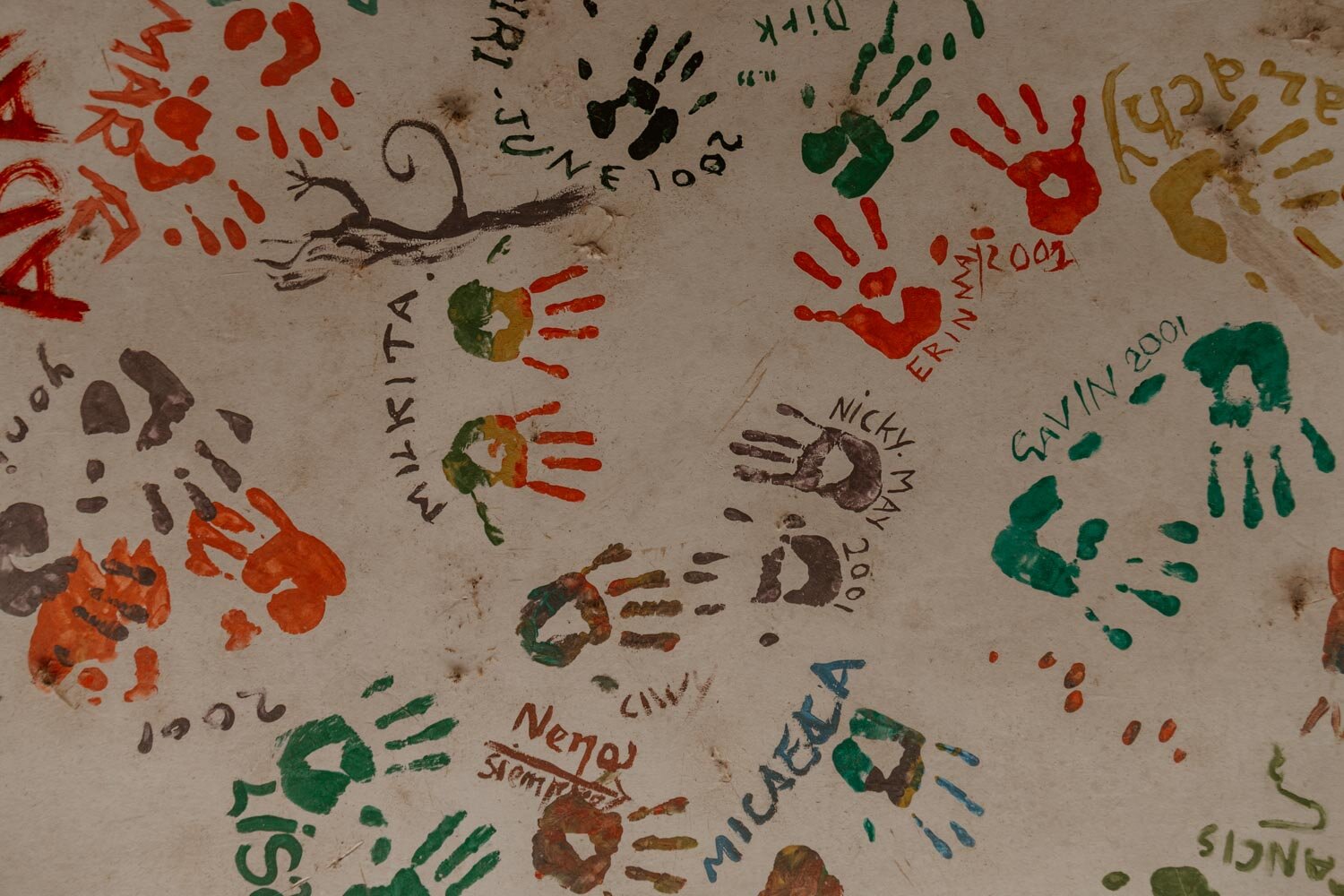

The founder of CIWY can always be found wearing a sweat-dampened old t-shirt, mud-splattered boots and a well-worn baseball cap. Her name is Nena, and her journey to open her three animal rescue centres started with a monkey which shared her name. On a visit to Rurrenabaque with others from the environmental movement, they found a group of tourists huddled in a circle, laughing, taking pictures. She joined the crowd to find that the attraction was a monkey - chained, chain smoking and with her only refreshment available being a can of beer.

The crowd lapped it up.

Nena found the person 'responsible' for the monkey and, after a tough negotiation, persuaded him to let her buy it. She didn't know what sort of life she would be able to give her, but she knew that anything would be a marked improvement from that.

Since that day, Nena and her team have taken in hundreds of animals. Just over four hundred in fact. There's Octavo - a quiet solitary male spider monkey who is obsessed with zip-lining. Chuki the capuchin whose squint and gradually-stiffening jaw bears the scars of when he took a bullet in the face from poachers who killed his mother. The dishevelled parrot Motacito, who hobbles, squawks and gossips at passers-by from the ground as his wing was broken by children who had him as a pet. Dozens of curious coatis who were kept as pets then gradually abandoned as their cuteness transformed into something much less appealing. From turtles and colourful birds to jaguars and pumas - all have found an escape from a sad past, as well as a home, here.

The heat is the first thing the strikes you in Villa Tunari - it washes over you, catches your breath and makes you perspire endlessly. It makes a cold beer at the end of the day in the small cafe for staff taste all the sweeter. It's there that we chat to some volunteers. The common tongue here at Parque Machía (one of CIWY's three refuges) is English, rather than Spanish, and they hail from all parts of the globe - France, Israel, the US, UK, Australia, Switzerland, Chile. Those who have only been here a few days are easy to spot; their branded t-shirt is still relatively clean, their welly boots spotless, their senses still adjusting to everything around them. But there are others who are clearly long-termers, those utterly comfortable and at home in the basic surroundings and sticky afternoon heat.

One of those is a male member of group responsible for walking and feeding Baloo the bear. He was first here in 2012 and has returned for another six-month volunteer stint. “I haven’t missed anyone like I missed Baloo” he tells us. The former circus 'performer' was the main reason this volunteer came back to Bolivia and, in our short conversation around the table, his love for the animal shines through. Even though the climate in this part of the world isn't Baloo's natural environment, there was simply nowhere else to go for him after being rescued from the cruelty of the circus and his happiness depends on people, like this volunteer, brave enough to escort him on walks or to take him swimming.

The volunteers here form tremendously strong connections with the animals they are assigned to look after for weeks or months. The smiling Australian vet volunteer who took us up the hill to the group of free and semi-free Spider Monkeys, with buckets of bananas and bottles of api on our back, had also just returned for her second stint of six months. Although the monkeys are an indistinguishable group to us, she knows each by name, knows their personalities, knows their group dynamic and their character traits. "You fall in love with them all", she says and her affinity for the group she spends around eight hours with every day is clear.

We ask them all what you need to be a volunteer here.

A love of animals is the first response and, although that may seem like it's stating the obvious, a few days at the refuge reveals that the love they speak of is something deeper than the usual. It's not simply an ephemeral cuddly, instagram worthy love - the sort where you love laughing at funny dog videos but never actually have picked up their shit - but a deep set empathy for them. CIWY is notorious on the backpacker circuit as somewhere where selected volunteers will be able to walk a bear or a jaguar - but those coming only with that and future bragging rights in mind would not be welcome. And they probably wouldn't last.

The digs here are basic, the daily routine is tough and the hours are long - this is a gig for people who really want it, who will be dedicated to the work rather than those who simply want to say they helped some animals in a foreign country and got a selfie with a monkey.

All is not perfect here at this refuge though and there are no doubt many things that could, and should, improve.

Most evident, is the problem of aesthetics. We reckon that each and every first-time visitor will jar at the sight of the cages, collars, the runner system and the ramshackle state of some of the facilities. A number of the cages are old, rusty and rickety and can look like the sort one may expect to find at a bad zoo, not an animal refuge. Space is also at a premium meaning that to many, it may appear that there are simply too many animals in one spot. A number of these elements are wholly necessary for the safety of both animals and volunteers, but it's definitely something that surprised us.

However, on deeper exploration, they are issues stemming from financial restriction, rather than any form of neglect or lack of care or concern. CIWY depends heavily upon the donations of volunteers, the public and non-profits - in fact, that’s all they have. They operate on a shoe-string and put the money they do have towards feeding and caring for the animals. For some context of how much that costs, the monthly food budget for the animals is £2,000.

And this, let's remember, is £2,000 in Bolivia.

In the past, they were able to dedicate a small number staff and resources to educating Bolivians about animal welfare however, due to lack of funding, that is simply no longer possible. And, with so few other options for rescued and formerly captive animals in the country, for the first time in years, CIWY has having to tell the government that they simply do not have any more space.

From our time spent here - asking questions, seeking answers - we have no doubt that their hearts are very much in the right place and, if more money was available, it would be put directly towards the animals. Nena is the first to recognise the issues we highlight about some of the facilities and, when we ask her about them, her response is clear and genuine - if she had more money, she would put it all towards these improvements.

This is a key reason why the accommodation and facilities for volunteers are so spartan - they would rather put the funds toward making the animals' existence more comfortable.

We ask why she doesn't just take the easy option easy option to make some more money - open up parts of the centre to paying visitors? After all, we visited a park in Costa Rica - with similar values and rescue philosophy - which opened its doors for a few hours every day to hundreds of tourists (far too many in fact) and charged top dollar for the privilege, even to volunteers. Further down the road in Bolivia, another park operates a similar approach, including the opportunity to watch a bear being fed every morning.

For Nena, that is not at all the type of place she wants to run and, from her experienced perspective, it undermines the work she has done over the last few decades. The animals were taken here to be away from humans - to be safe - rather than to simply become another form of attraction. Bringing in tourists - many who would view the centre as just another zoo where they can poke, prod and take selfies with creatures - removes that barrier for the animals and would subject them to a whole new range of risks and deep-seated fears about unfettered human contact. It would also completely change the operation at the park.

And so, the costs of salaries, food for hundreds of animals and other operating expenses all have to be met from a limited pot of volunteer payments, donations and fundraising efforts. From our interactions with people around animals in South America (local and non-local) we both completely understand Nena's point of view. Although we enjoyed that park in Costa Rica, we both felt a little uneasy at its hybrid model where people could pay for the privilege of being around rescued monkeys and the numbers of people allowed in to such a small space. On the last day of our visit, when our guide Rosita took us to a mirador within the government's section of the park (where tourists are encouraged to pay and can come in without any supervision), we were confronted with a group of 40 people - men, women and children - surrounding one of CIWY's free spider monkeys.

She had been used to human contact, and a visit from her to this popular part of the tourist trail wasn't uncommon. However, you can imagine the type of scenes to which we were subjected. Groups of teens with selfie-sticks, mean-eyed children trying to get close enough to aim a little kick, amateur photographers with their flashes on, shouting and screaming; in short, a complete disregard for their own safety (a male spider monkey subjected to this would have been much less submissive), but this wild creature with a tragic past's well-being as well.

We advised, we lectured, we argued and yet, we received no apology from the tourists (we actually received a downright refusal to believe what they were were doing was wrong) and the whole lecture on basic decency around animals had to be repeated whenever a new group of day-trippers arrived. Thankfully, the monkey recognised Rosita and eventually let her lead her into safety - even though members of the crowd continued to try and get close enough for a photo.

Simply having the privilege of seeing a free monkey in the wild was not enough.

After three days full of emotion and a steep learning curve about some of the horrendous situations animals are subjected to in order to sate human desire for exotic pets or tourist fodder, this situation laid bare exactly how much progress is needed and why, for someone like Nena, allowing the animals near groups of tourists ever again is anathema.

In a country as poor as Bolivia, and with so many competing developmental issues, it isn't really a surprise that the financial assistance they provide to organisations like CIWY is next to nothing. Human poverty, although improving, is still rife in the country and there is a long way to go before it is eradicated and it's understandable that that has to be a focus for limited resources.

However, there are still aspects of stated policy around animal protection which confound us. For example, Bolivia was one of the first countries in the world to make owning an exotic or wild animal illegal (and we saw several posters promoting this in various cities), yet they allowed an unusable road (pretty much to nowhere) to be built through a section of Parque Machía park, ripping out a huge area of habitat for the animals resettled and native to there.

Not even Jane Goodall's support could prevent that.

The government also depends hugely on CIWY to take in the animals they confiscate from owners under the new protection law, and yet give them nothing towards their operating costs. In a bewildering turn of events, they have cultivated a section of Parque Machía into a tourist park (and therefore leading to encroachment on the animals in some areas) but none of the 5b entrance fee is given towards CIWY.

One of the key questions before we visited CIWY concerned the fact that very few of their animals are released back into the wild. From our perspective, surely it's better for these animals all to be put back out into their natural habitats as soon as they are healthy and able? Wouldn't that return to freedom make them happier?

Well, the situation is a little more complicated than that and, to understand it, we have to go back to basics. A number of the monkeys in places like CIWY were sourced from the jungle or rainforest when they were babies. By sourced we mean stolen, and by stolen, we mean ripped from their mother's arms after she had been shot. Poachers and hunters follow the same approach with big cats (yep, we had no idea either), which is why a baby jaguar arrived at the sanctuary's doorstep a few weeks prior to our visit. These stolen animals are then trafficked internally or internationally to be housed in exploitative zoos and circuses, sold as exotic pets in the black market (or sometimes even the actual regular Bolivian market) or to satisfy archaic, non-scientific medicinal approaches practiced throughout the world or simply for their pelts.

As they are taken at such a young age, they therefore grow up in environments so removed from their natural habitat and wild existence that the jungle comes to be a strange and dangerous place. From how to hunt or gather food, how to interact with other animals, how to swing from a tree or how to know their place in a pack hierarchy, they have not learned many behaviours which are essential to their natural role and position in the wild. To the human eye, they may seem like a monkey, smell like a monkey and act like a monkey; but that is only partly true.

Further, with so many having been raised by humans and used to their presence, there are a myriad of issues about releasing them anywhere near a habitat close to human settlement areas. You can imagine the outcome of a jaguar, raised on a diet of bottled-milk and human dependency, wandering too close to the local village in search of the human company it has been brought up on. And with with illegal poachers still operating with impunity, these released animals would be very easy target (in the press during our visit was a Chinese visitor who was found with twenty SETS of jaguar teeth in his bag). According to a science advisor for WWF - "There's no point releasing it if someone is going to come and shoot it two days later."

Moreover, to assume that putting a captive-bred monkey into the wild is a simple process is, simply, wrong. According to one expert, it is a 'majorly flawed ideal'. Monkeys are not lone rangers in the wild - they need to be part of a group with a rigid hierarchy - and there is no guarantee that they will be accepted within the pre-existing free monkeys' arrangements. With males, it is also likely that they will be viewed as a competitor to the alpha, and that is only going to end with one winner.

Aside from considering the well-being and safety of the released animal, significant research and consideration has to be put into protecting the wild populations and ecosystems to which it is being released. Will it negatively affect the genetic make-up of wild animals? Will it be an invader species? Will it compete for scant resources or introduce disease into the wild population?

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, all the animals in animal rescue institutions in Bolivia are actually the property of the government and it is illegal to release them back into to the wild.

So, organisations like CIWY try and make do. They try and give these animals - rescued from basements, circuses, roadside zoos, family homes and dingy market cages - a second chance in a safe and caring environment. And, some animals do actually make it out if they are suitable and able. With the spider monkeys, those up in the lush green hills whom we visited with api and bananas, CIWY have managed to create an environment where new arrivals are, slowly, introduced to the group which resides here. It often doesn't work - rivalries and irrational dislikes are normal amongst monkeys - but, sometimes, a magical thing happens. We were actually lucky enough to witness one female, who had been carefully integrated and accepted, being released into this free population.

It was a beautiful yet bittersweet even to witness as we knew that this was the exception, rather than the, entirely understandable, rule.

Amongst the international volunteers at CIWY, there is a small core of Bolivian permanent staff. One of them guided us from the hidden away spot in the trees which the spider monkeys call home. When he was a young boy, orphaned, he ended up lost in Villa Tunari and was told to go to the park where the animals were. Taken in by Nena and her team, he grew up amongst the animals and to watch him with them is a thing of pure, raw beauty.

On our walk, he tells us that he always wanted to be a lawyer with "a big car and two girlfriends". Now he's studying to be a vet and has no doubt as to where he will come back to in order to use his skills. "People come here expecting to change the animals' lives, but they change ours", he smiles.

One volunteer, Swedish with long hair and a straggly black beard, is sporting a rather fresh-looking tattoo of a jaguar as he sits with the others at lunch. Although he and his friend only planned to have a three-week stint here as part of their South American adventure, they both decided to completely change their itineraries and after a few weeks away, have returned to devote the majority of their travel time to working at a couple of CIWY's refuges.

As the Australian vet told us on our first day, the volunteers really do fall in love with these animals and, after understanding the tragic and cruel background of each one at Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi, to know that they now have a place where they are not only safe and respected as animals, but also loved, is perhaps the best second chance they could hope for.

want to know more or volunteer?

Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi is always looking for travellers to help them across their three sites in Bolivia. A minimum commitment of two weeks is required and a weekly fee is charged (much lower than similar organisations in Bolivia and elsewhere in Latin America). The accommodation is basic and the work is hard but, each and every single volunteer there is required and won't be there to just make up the numbers. Training is given once you arrive.

To find out more, check out their website or if you would like to donate to them, go to Friends of Inti Wara Yassi.

For more information on how to travel in a more ethical way, read this post and if you would like to know more about animal friendly travel and how you can help, check out World Animal Protection.

** All photographs were taken by us were under the supervision of an experienced member of Inti Wara Yassi's staff. We were wholly respectful of the animals and their personal space and only took photographs when safe and appropriate for both us and them. Whenever you photograph animals, please do not use flash and be respectful of them and your surroundings at all times.

All opinions in this article are our own.