Wander around a few of the streets in an eastern pocket of Guatemala and dreadlocks will be a more common sight than more traditional Latino garb of cowboy hats, blue denims and well-worn leather boots.

Turn the corner and the echoes of drumming and melodies will sound unmistakably African.

Here in Livingston, as well as parts of Honduras, Nicaragua and Belize, the vibe is distinctly Afro-Caribbean. The reason is the Garifuna – an enduring set of survivors who escaped the slave trade on countless occasions.

Their story is one of periods of survival, migration and cultural endurance in search of a permanent homeland, blending influences from the Caribbean, South America and Western Africa.

In the 16th century, European states had hit upon the idea that the valuable commodities of the New World – such as sugar, cotton and coffee – were best harvested by treating their fellow man as a lesser commodity. Transported in rudimentary cargo ships, thousands of slaves were ferried to Central America to face a life of servitude and subjugation. On a tortuous voyage up to one third died before reaching land with poor hygiene, dysentery and dehydration claiming the lives of many whilst, faced with pirates and rough seas, there were numerous ships that simply disappeared.

The origins of the Garifuna are uncertain, with two contending theories explaining the arrival of Africans in Central America.

The most prevalent account centres around the shipwreck of a slave ship. It is thought two Spanish ships carrying their 'cargo' of West Africans (thought to be Nigerians) floundered in the Bight of Biafra in 1635. The wreck took its toll but those who survived and escaped (both the incident and certain slavery) made it to Saint Vincent.

The opposing theory centres around an expedition by 14th century Malian King and explorer Abu Bakr, who some believe discovered America nearly 200 years before Columbus. Through his voyages, the first Africans settled on the island.

Regardless of origins, the newcomers were welcomed by the local population of Carib Indians as equals and lived in relative harmony. Inter-marriage was common, and the proceeding generations were to be known, and identify with the term, 'Garifuna'.

However in 1793, following years of unrest between the French and British, the Treaty of Paris decreed St Vincent a British sovereign.

The Garifuna were aware the servitude their antecedents had avoided was all too likely a renewed possibility, so a sustained campaign of colonial resistance, rebellion and disobedience was mounted. Previous efforts had been successfully launched against the French and the British.

British reinforcements sought to subdue the 'rogue element' of the island and eventually overpowered the Garifuna and, considering them infidels, expropriated the survivors - thought to number between 1,500 - 5,000 - to the island of Roatan.

From here, necessitated by hostile terrain and an inability to flourish on the meagre rations supplied by the British, the Garifuna quickly migrated to mainland Honduras where continued population growth allowed them to re-establish themselves, with many relocating to the Caribbean coasts of Belize, Guatemala, Nicaragua.

Recent figures number the global Garifuna population at around 300,000. The majority are still based in Central America, but a large diaspora has settled in the United States, particularly in New York.

Music

UNESCO, in 2001, declared 'Garifuna Nation's' language, dance and music in Belize to be a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity".

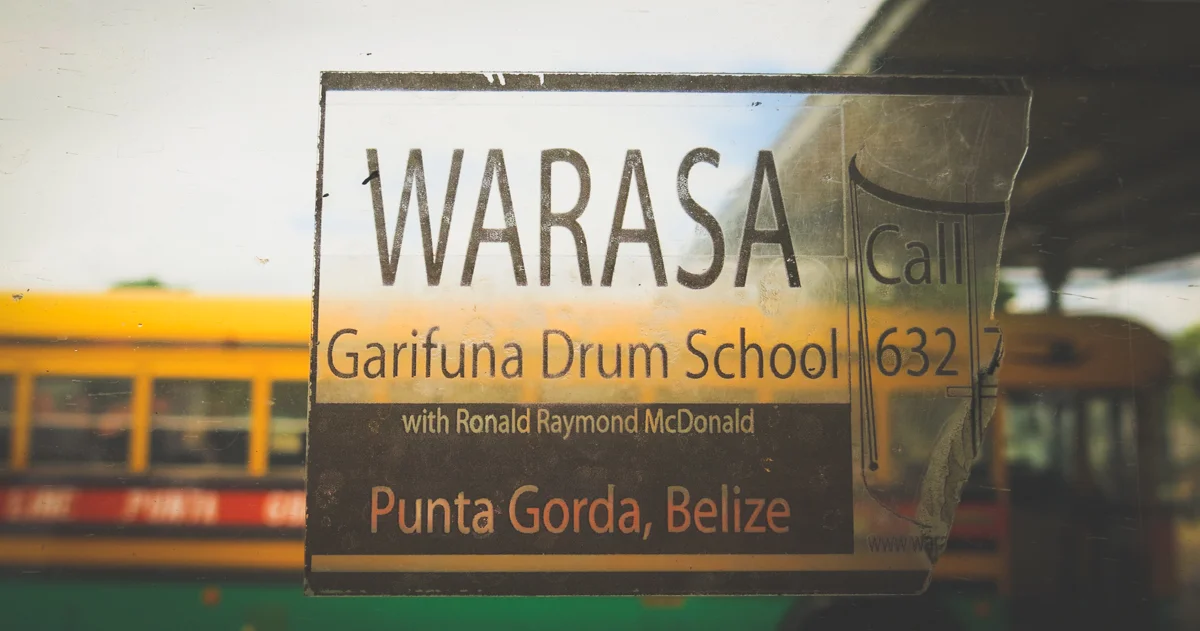

A key reason for this is that, as slavery was avoided a various junctures, anthropologists have argued that the Garifuna are the only black people in the Americas to have maintained a direct line to their ancestors' original Afro-Caribbean culture. This is perhaps best preserved in the musical staples of Garifuna music – pulsating drums and call-response lyrics.

The two main drum types are the primera and segunda - the lead and the accompanying bass. Sometimes traditional percussion such as turtle shell and conch will still be used.

Rutilla Figueroa wrote "The Garifuna sing their pain. They sing about their concerns. They sing about what's going on. We dance when there is a death. It's a tradition to bring a little joy to the family but every song has a different meaining. Different words. The Garifuna do not sing about love. The Garifuna sing about things that reach your heart."

A more recent musical genre is Punta Rock, commencing in the '70s, an evolution of traditional folk songs but often with more modern rhythms, concerns and instruments.

After a few nights out in Belize and Livingston, even the most reluctant dancer will find it hard to resist joining in with the energetic and sensual dancing which often accompanies the music.

One of our favourite Garfiuna muscial pioneers, Ideal (Photo credit to David Hill)

Language

Garifuna contains a number of words of Arawak and Carib origin, as well as loan words from Spanish, French and English. Though Spanish and often English is widely spoken amongst Garifuna, is still frequently spoken amongst communities across Central America. To give a flavour of the language, some examples are below:

Good morning. Buiti binafi.

How are you? Ida biangi?

What is your name? Ka biri?

My name is Simon Simon niri bai

For fear of the language being sidelined by younger generations, a number of efforts are being undertaken to preserve and promote Garifuna language and culture, such as by The Garifuna Institute and Rasta Mesa.

The thing that struck us most on our travels was the deep sense of community and history amongst the people we met. From almost ceasing to exist 300 years ago, it is a thing to treasure that such a strong Garifuna identity lives on in music, dance and language.