I have a confession to make.

For the best part of my childhood to my mid teens, I spent an embarrassingly high proportion of Friday and Saturday nights on my own watching men in lycra covered in baby oil grapple with each other on late-night satellite TV.

Sometimes my friends and I would re-enact what we saw in our bedrooms, not telling our parents because they thought it was too dangerous and would be, perhaps, slightly ashamed of us.

I'm talking about wrestling - the WWE specifically (WWF as it was known in those days).

Most of my childhood heroes had names such as The Undertaker, The British Bulldog, Bret 'The Hitman' Hart and The Rock; my 6th birthday cake was a mock-up of the ring with strawberry laces acting as the ropes; my older brother and I staged Battle Royales and kicked lumps out of each other; and to this day, I have refused to let my mother throw out my bag of 350 wrestling figures, whose names and finishing moves are engrained in my memory.

Eventually, the weekend entertainment provided by wrestling evolved into more socially acceptable forms of activity such as under-18 discos and getting drunk on 4 cans of Tennents Lager. But, when Emily and I were planning our route through Mexico, I jumped at the chance to get nostalgic and spend an evening with some of Mexico's iconic luchadores.

Known for its colourful costumes, high-flying manoeuvres and pantomime antics, Lucha Libre (free fight) is a Mexican institution, as globally recognised as the taco or a donkey called Jose in a sombrero. If further proof was needed its place in the national psyche, one only needs to study the crowds of this summer's Mexican World Cup matches where, when the camera man wasn't settling upon beautiful women, he had scoped out yet another wrestling costume in the colours of El Tri.

Following an afternoon indulging in fish tacos and cheap beer, we arrive upon Guadalajara's CMLL Coliseum with an hour and a half to spare. It is still early, but the street is already bustling with families, old men and groupies ready for action. Most of the children are begging their parents to be taken to the shop opposite so they can be kitted out in the mask of their hero; for it is the mask - which comes in a range of styles, from glittery Power Ranger to gimp - which is the most recognisable and important symbol in Mexican wrestling and its significance cannot be underestimated.

Little did we know it, but this young woman turned out to be most mental wrestling fan in Mexico.

The mask is a luchadore's identity and public persona and transforms him from a man on the street into a superhero or super-villain.

Its influence on the sport is best encapsulated by one of the Mexican greats – El Santo. Movies, cartoons and comic-books were made about him, but throughout his four-decade career his identity was never known; his adoring fans had no idea who was the man behind the silver and white mask.

Only once, for a fleeting moment following his retirement, did he remove the mask in public. It became so integral to his being that he was buried in it.

El Santo's story is not the exception, but instead underlines how entwined a performer becomes with his character.

The plaques and obituaries around the Arena Coliseo immortalise the characters and their lifetime, rather than that of the men. At our show, we see several wrestlers pull up to the arena and all wear their masks to maintain their mystique and anonymity.

We take our seats in the 4th row in time for the first match. Kids are squealing with excitement, running to the ring for autographs and high-fives after each entrance. A well-heeled elderly couple take their seats in front of us and man, who must be in his 80s, ambles to his seat, waving a greeting to the other regulars.

Each match consists of 'faces' (good guys) and 'heels' (bad guys). The faces tonight tend to be the younger, more handsome wrestlers with a high-octane style, whilst the heels are more sluggish and thuggish, ignoring children on their walk down the aisle and giving abuse to the crowd.

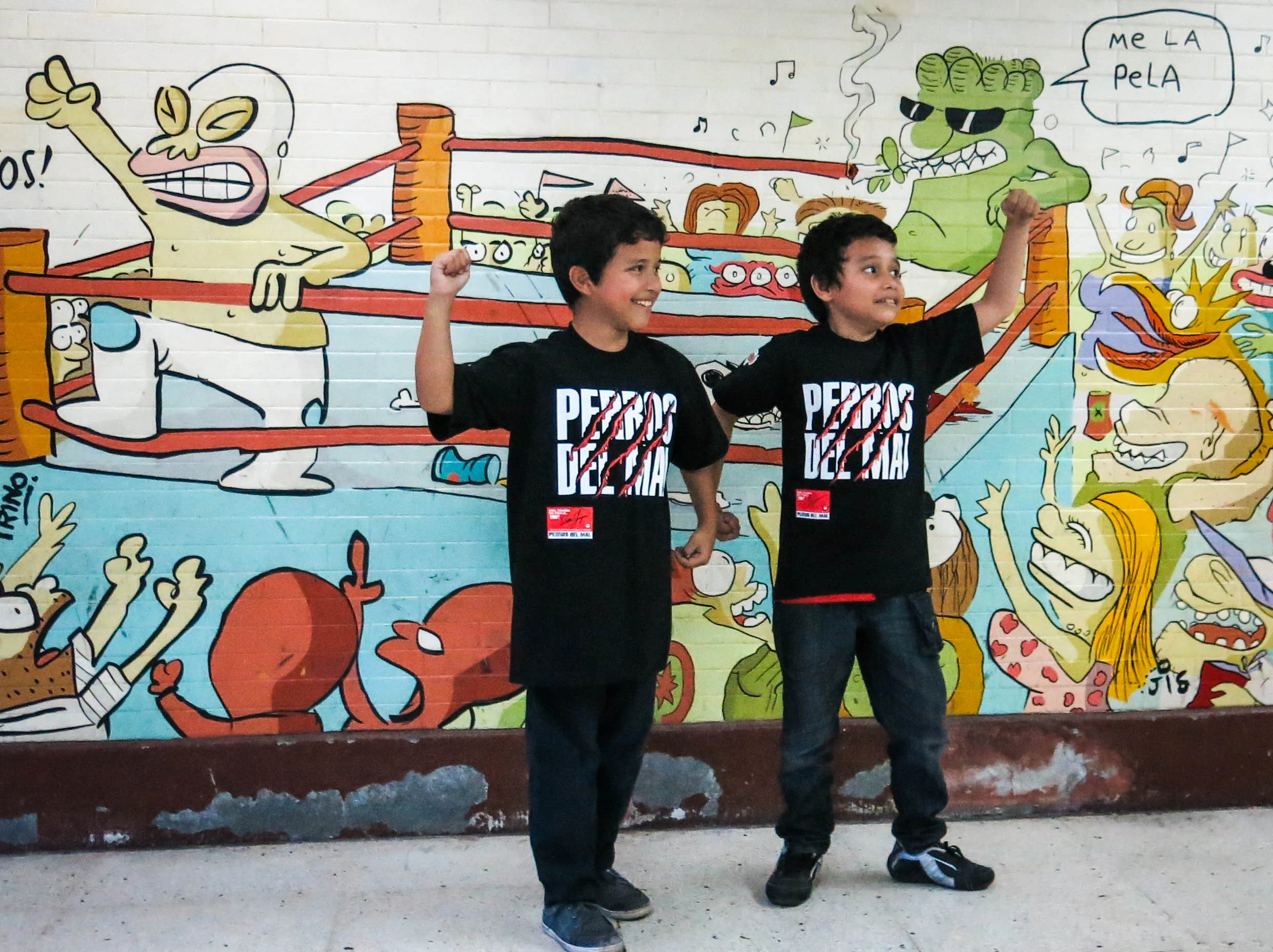

Young wrestling fans.

The action is fast, physical and acrobatic. At least once a match, one athlete will leap headfirst through the ropes – often with a couple of twists thrown in – to clatter into his opponent and a few fans. Tonight one couple sees their freshly purchased beers and popcorn sent flying. It's for this reason that pregnant women and children under five are banned from sitting in the first three rows.

The crowd is passionate and involved. The boos ring out when the crooked referee is clearly counting the pinfall slowly to help out the 'heel' and the cheers deafen when 'face' El Divino comes back from near-death to put his finisher on Joker to win the match.

There is an old lady to our right, and a young woman to our left – both on their own – constantly hurling abuse and flipping the bird at the bad guys, goading them into an argument and screaming when their favourite is floored.

A child behind cries when her hero is attacked by two opponents. Another runs up the aisle to tell off Shocker for being mean to everyone.

One man is removed for throwing his beer at Sanson and a father embarrasses his young son by being physically restrained by security after trying to attack the cheating referee.

And then - after six matches - the show ends, the lights come back on and everyone in the crowd returns to normal.

The majority of criticism about the wrestling industry is that it's make-believe. Of course, it is true that results are staged, the kicks, slaps and punches are dramatised and no-one is intentionally hurt.

Getting up close however - hearing body meet ground and counting the surgical scars - provides a stark reminder that the physical sacrifice and risks that these men confront is no fairytale; paralysis or a fatality is only one high-risk mistake away.

The locals are enthralled with the theatre of it all – the crowd cuts across class, gender and age. Why do the Mexican public enjoy wrestling?

The entertainment and unpretentious fun of it are certainly key reasons – even Emily the sceptic started to lose herself and gasp at some of the more impressive high-flying moves. I'll also admit that, as the lights dimmed at 6 p.m and the first wrestler's entrance music kicked-in, the child inside me was coming to the fore for the first time in years; as sad as it sounds, wrestling, strawberry Chewits and Jet from Gladiators are probably the only three things that will ever achieve that.

But, perhaps on a deeper level this comic-book world provides escapism and a place where many can leave reality at the door. Some people have soap-operas, others Game of Thrones, but everyone needs some form of entertainment which removes them from the realities of the daily grind.

In Mexico's wrestling rings, it is clear who is good and who is bad, and the good – unlike real life - will always prevail in the end. As young luchador Máscara Celestial said, “I love my character — a good character in a very difficult world".

Ticket Information

If you're in Mexico, a wrestling show is a great cultural and entertainment event. Mexico City and Guadalajara are the main venues - with shows on most Tuesday and Sunday evenings - however there are shows around the country.

Tickets for CMLL in Guadalajara and Mexico City range from $50-130 MX per person ($10 for children). The cheaper balcony tickets are perfectly good for enjoying the show, but spending more does get you closer to the action. Unfortunately, you are not allowed to take pictures inside the arena and this is quite strictly enforced.

For future shows and ticket purchase, visit CMLL or Ticketmaster.